AUTHOR: Thorfinn Stainforth

The revised multiannual financial framework (MFF) and the recovery package announced by the European Commission include €55 billion of new funding for the cohesion policy.

This proposed increase, which amounts to about 13% extra compared to the planned total for the 2021-27 MFF, is an important signal when the entire EU project is at risk due to clashing visions of what European solidarity means in the post-COVID-19 context.

Glueing Europe back together

One of the EU’s foundational objectives is to strengthen internal social, economic, and territorial cohesion by addressing regional development disparities.

Cohesion policy, one of the EU’s most important areas of action rivalled only by agriculture in budgetary terms, is thus at the heart of a fundamental “political bargain” that has shaped the EU so far.

| It is important to strike a new “contract” between rich and poor countries in Europe, based on quantitative targets for economic, social and ecological convergence |

Although progress has been made in purely economic terms, different regions and countries face new and unprecedented challenges related to climate change, inequality, and pandemic recovery.

Within this context, it is important to strike a new “contract” between rich and poor countries in Europe, based on quantitative targets for economic, social and ecological convergence. This will require:

- A holistic approach to convergence – based on the SDGs, not just income inequality.

- A new commitment from those countries that benefit from cohesion funding and have slowed down progress on climate action to change their approach – responsibility for convergence starts at home.

- A commitment from wealthier nations to do their fair share in terms of financing but also making technologies relevant and available to poorer parts of Europe.

An unequal continent

The challenges faced by the EU, and our capability to mitigate and adapt to them, are still very regionally stratified. Despite an overall reduction in economic disparities, north-south and west-east divides between EU countries remain, and these inequalities are broadly reflected in other fields of economic performance, such as employment, R&D expenditure, and resource productivity.

Wealth is regionally concentrated in the EU, with just 97 out of 281 regions* recording a level of GDP per inhabitant that is equal to or above the EU-28 average. Although wealth is generally concentrated in Northwest Europe, it is notable that capital cities across the EU are centres of wealth, and the contrast is particularly stark in the eastern Member States.

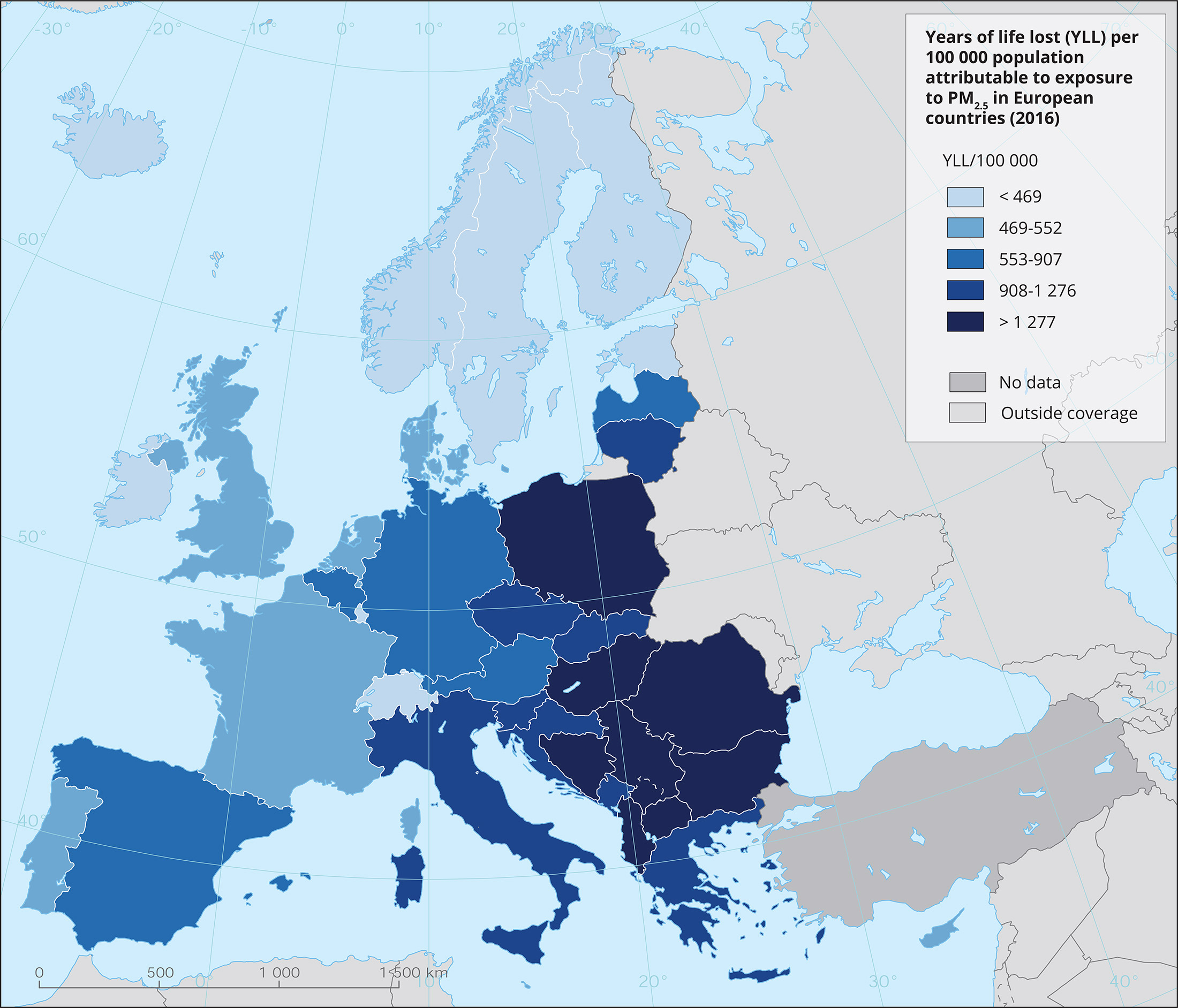

Figure 1: Years of life lost per 100 000 population attributable to exposure to particulate matter in European countries. (Source: European Environment Agency) Figure 1: Years of life lost per 100 000 population attributable to exposure to particulate matter in European countries. (Source: European Environment Agency) |

Environmental degradation is already disproportionately affecting some parts of Europe.

The life expectancy of citizens from Central and Eastern Europe, for instance, is more severely affected by air pollution than in Western Europe, with estimated years of life lost three times as high in those regions than in other parts of Europe (see figure 1 above).

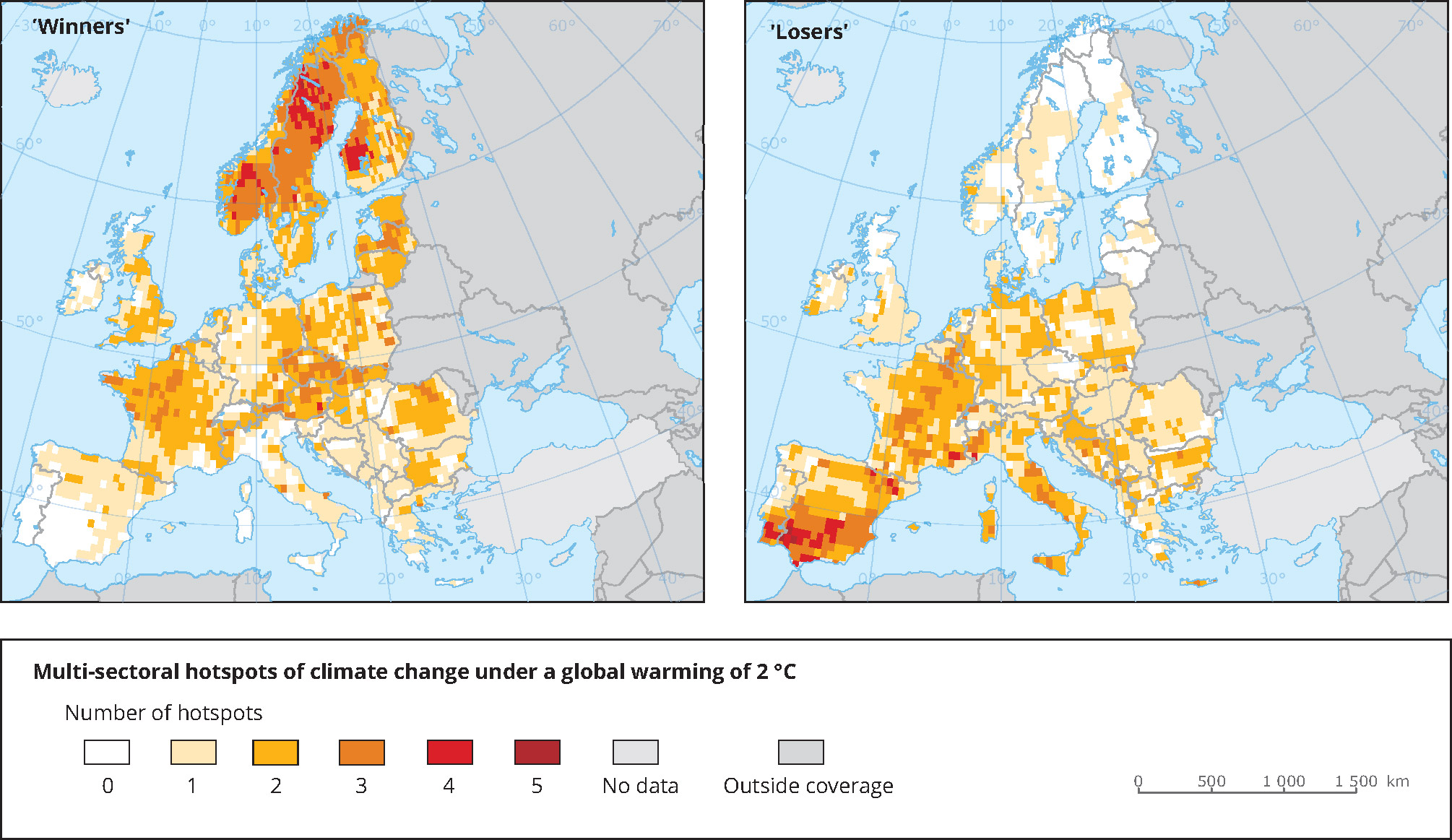

Forthcoming impacts of the climate emergency vary considerably across the EU, with the worst affected regions primarily in the Arctic, Southern Europe, and coastal and mountain regions. Should current trajectories of emissions persist, parts of Southern Europe are expected to experience extreme heat events once every two years and yields of rain-fed maize are expected to decrease by 50%.

These differentiated impacts, as illustrated by figure 2 below could contribute to creating further divergence – rather than convergence – in the EU.

Figure 2: Maps showing the projected climate impacts under two-degree warming on the water, agriculture, ecosystems and human health sectors. (Source: European Environment Agency) Figure 2: Maps showing the projected climate impacts under two-degree warming on the water, agriculture, ecosystems and human health sectors. (Source: European Environment Agency) |

Towards a new cohesion policy

That is why we need a renewed focus on a bargain between the wealthiest regions and countries with the most capacity to address these challenges and those with the least.

| The proposed increase in cohesion funding and intention to build more resilient and sustainable economies represent a significant opportunity |

The proposed increase in cohesion funding and the stated intention to build more resilient and sustainable economies in the crisis repair phase represent a significant opportunity to do so, assisting vulnerable regions and countries to phase out the brown economy, create a new sector of activity and build greater resilience to forthcoming shocks.

The Commission’s original MFF proposal from 2018 included a cut in real cohesion funding levels. However, the increase proposed in May would compensate for that cut – and increase it slightly. When increased funding for the Just Transition Mechanism (now a baseline of €40 billion in new funding) is accounted for, it is fair to say that cohesion funding has been significantly increased.

Cohesion funding continues to be an important framework for addressing the fundamental long-term challenges of the European Union.

| Cohesion funding continues to be an important framework for addressing the fundamental long-term challenges of the European Union. |

The Just Transition Mechanism, whose funding is also increased in the new proposal from the European Commission, can play an important part, and its resources should be scaled up – as the Commission has proposed.

The allocation formula under the mechanism is currently very heavily focused on coal mining and traditional heavy industry. While these are important sectors, they are by no means the only ones that will need assistance for a truly just transition. Areas heavily dependent on, for example, the aviation sector or car manufacturing could also be considered for inclusion in the formula.

The focus of the European Commission on addressing youth unemployment through cohesion funding is clearly important and addresses one of the great crises of European public policy.

Indeed, the issue of inter-generational justice needs to be considered throughout the cohesion policy, as investments made today are needed to protect young people and future generations from an ecological and social debt that we will otherwise pass on to them.

Empty street in Sofia, Bulgaria, during the COVID-19 lockdown © Nikolay Doychinov/European Union Empty street in Sofia, Bulgaria, during the COVID-19 lockdown © Nikolay Doychinov/European Union |

Recommendations

The following recommendations are important points to ensure that the cohesion policy can be used to its full potential in confronting the crises and vulnerabilities outlined above:

| Targets | The EU should adopt specific overarching convergence targets related to closing the gap between countries on income inequality and pollution. These can further help to clarify objectives and programming decisions and bring enhanced transparency and accountability to the process, as, for example, the energy and climate targets have. |

| Scale | The IPCC has shown that the coming decade will be a ‘make or break’ time in determining if we can achieve the Paris Agreement’s warming objectives. The primarily northern countries whose populations and governments claim to be so committed to climate action must rise to the challenge and provide the resources to make this initiative a success. The countries of southern and eastern Europe must take advantage of the opportunity to transition their economies on time. |

| Results | Cohesion funding should be made more results-oriented and closely linked to the national energy and climate plans (NECPs) and EU climate and energy goals. One criticism of the funding is that it is still not results-oriented. Mechanisms should be put in place to ensure that countries which are achieving – or over-achieving – their targets are rewarded. |

| Fossil fuel exclusion | One of the main points of controversy under cohesion funding has to do with the exclusion of fossil fuel funding from eligibility. The European Parliament has voted to exclude fossil fuels, including gas, from funding under the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF). However, the Council continues to argue for fossil fuel funding, and it is unclear where the final negotiations will end. European funds must not continue to lock-in new fossil fuel infrastructure over the next decade. |

| Earmarking | Despite the current earmarking, allocations towards renewable energy and energy savings remain low, so the Thematic Concentration for the ‘transition to a green, low-carbon Europe’ (Policy Objective 2) for Cohesion Policy 2021-2027 should increase to 40%. |

| Win-win policies | Cohesion policy must build a bridge between the social and environmental dimensions of sustainability through sectoral initiatives to put “those further behind first”, including free low-carbon public transport in urban areas; green social housing programmes; priority air pollution action plans for the most affected communities; innovative solutions to remove barriers to mobility for the rural poor; addressing food deserts and the lack of affordability of healthy and sustainable food such as fruits and vegetables; and renovation requirements for the sale or rental of energy-efficient properties poverty. |

| Building renovation | Cohesion funding and the ‘renovation wave’ promised by the Green Deal need to be fully connected and implemented at scale to ensure energy-efficient building renovation. This is one of the most promising policies, with multiple co-benefits, including for employment, energy poverty, and adaptation if implemented properly. |

| Green taxonomy | The Commission’s action plan on financing sustainable growth is an important step toward fostering sustainable investments. Private financing is still a very important part of any investments made in less developed regions, and the new sustainable green taxonomy will be a key part of guiding such investments. Delegated acts implementing these guidelines are now being prepared by the Commission. Their final details will be critical. The criteria adopted under these delegated acts could help form the basis for future funding allocation decisions. |

| Local involvement and institutional capacity | Use territorial just transition plans as a way to work directly with local and regional governments, as proposed, for example, by some mayors in Visegrád countries, and to consult with the local population and stakeholders, including workers and their representatives as part of an enhanced social dialogue. Cities and municipalities should be given the space they need to experiment with inclusive decarbonisation, to kick-start change, which can be subsequently scaled up. It will also be important to build administrative capacity to help them, as this is an important factor in the successful implementation of cohesion funding. |

Thorfinn Stainforth is a policy analyst in IEEP’s Low-carbon Circular Economy Programme

_______

* 281 regions for which data were available in 2017