The EU has made strides in its quest to curb domestic greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) by setting clear goals and binding targets in legislation packages such as Fit for 55 aiming to reduce GHG by 55% by 2030. The EU also published on 6 February a communication on its future Climate targets for 2040, calling for a 90% net GHG emissions reduction compared to 1990 levels.

To remain a leader in effective climate policy, the EU, however also needs to address emissions generated abroad resulting from the EU’s appetite for imported goods in the same way. To bring these consumption-based emissions more strongly into focus in European policy, SEI and IEEP brought together key policymakers in an event hosted by Pär Holmgren (MEP, Sweden, Green Party) and Sara Matthieu (MEP, Belgium, Green Party) to highlight opportunities for action.

Despite decreasing domestic emissions, EU consumption footprint is on the rise

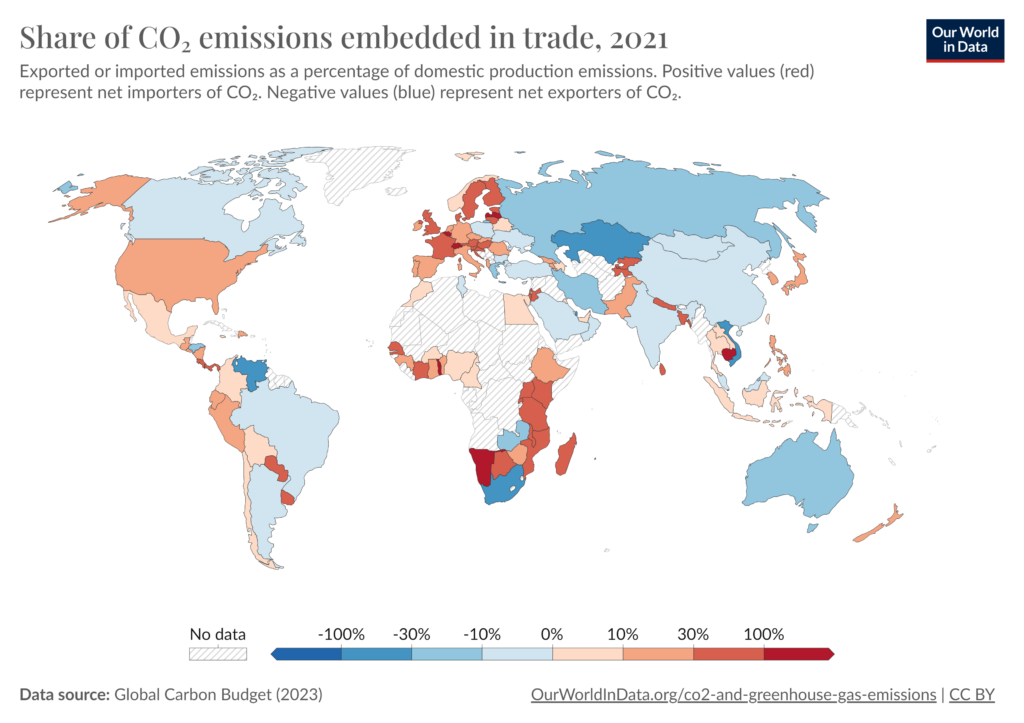

Since the 90’s, greenhouse gas emissions worldwide have increased by 63%, while the EU’s domestic emissions have decreased by 29%. However, this shows us only part of the picture: EU imports more emissions than it exports, pointing to a more significant environmental impact occurring outside of its borders in response to EU demand for imported goods and services. It is well documented that the EU tends to generate relatively large negative spillover effects compared with other world regions.

Figure 1. Source: Global Carbon Budget (2023) – with major processing by Our World in Data

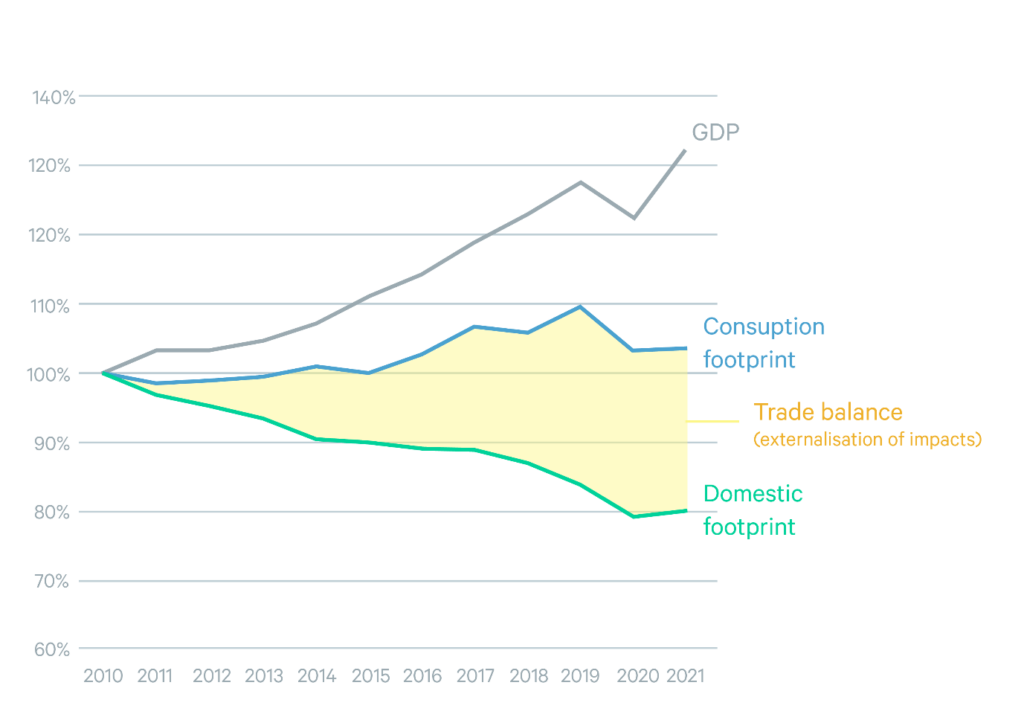

Despite domestic reductions, the EU’s consumption-based emissions actually show a slight upwards trend, emphasizing the need for a closer look at its consumption patterns and more sustainable practices on a global scale.

Figure 2. Adapted from Sanye Mengual & Sala (2023) Science for policy report. Learn more about the methodology and indicators used here.

These unsustainable consumption patterns are widespread throughout the EU economy as shown in figures 3 below, with textile & clothing and gas extraction the two main impactful sectors in terms of GHG emissions.

| GHG Emissions | Deforestation | Water Stress |

| Textiles & Clothing (8%) | Forestry & Logging (17%) | Textiles & Clothing (12%) |

| Gas Extraction (6%) | Beverage Crops (13%) | Food Products & Other Feeds (7%) |

| Motor Vehicles & Trailers (5%) | Cattle (5%) | Vegetable Products (5%) |

| Electronics & Precision Instruments (5%) | Fruits & Nuts (4%) | Fruits & Nuts (5%) |

| Furniture & Other Manufacturing (4%) | Furniture & Other Manufacturing (4%) | Leguminous Crops & Oil Seeds (4%) |

| Civil Engineering Construction (4%) | Hospitality (3%) | Fruit Products (3%) |

| Machinery & Equipment (4%) | Textiles & Clothing (3%) | Hospitality (3%) |

| Health & Social Work Activities (4%) | Building Construction (3%) | Sugar, Chocolate, Confection (3%) |

| Building Construction (4%) | Civil Engineering Construction (3%) | Rice (2%) |

| Wholesale & Retail; Vehicle Repair (3%) | Sawmill Products (3%) | Furniture & Other Manufacturing (2%) |

Figure 3. Adapted from Lafortune et al (2024). Trade-related spillover impacts from EU demand, by impact area and final consumer goods or services (top ten, %).

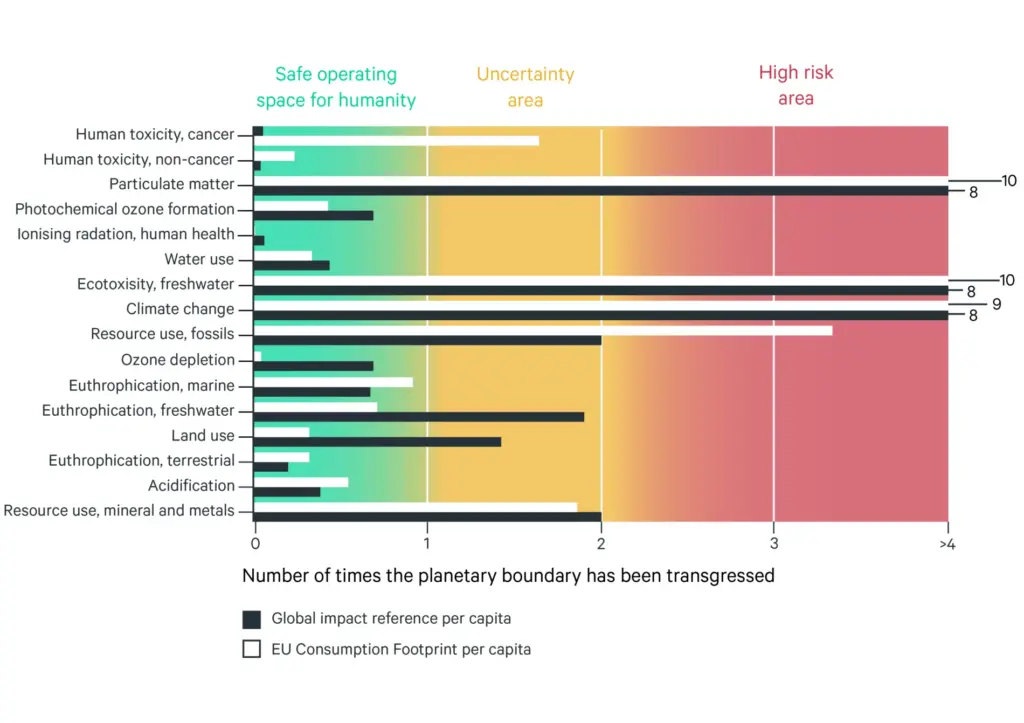

Beyond climate impact, it is key to shift EU’s consumption patterns as they currently fuel the transgression of other planetary boundaries with levels of particulate matter, freshwater use and use of fossils accompanying climate change in the high-risk area while use of minerals and metals are in the uncertainty area.

Figure 4. Adapted from Sanye Mengual & Sala (2023) Science for policy report. Learn more about the methodology and the indicators used here.

There seem to be two trends behind these consumption patterns, pulling in different directions. The main driver behind the increasing demand in imported goods is simply Member States’ growing population and affluence; wealthier European countries have higher consumption rates. The opposite trend driving down emissions within the EU is due to improvements in production efficiency meaning that we are using resources more sustainably and polluting less along the way. However, so far, improvements in the production processes have not been enough to offset the growing demand, resulting in the increasing consumption footprint.

There are ways to address consumption-based emissions on the EU and Member State level by:

- Monitoring consumption trends and their environmental impact

- Targeting specific mitigation goals to set a clear ambition and provide certainty to governments at all levels as well as businesses

- Identifying consumption hotspots to help tailor policy responses

- Testing green transition scenarios, taking lifestyle and behavioural change into account

- Reducing demand with more durable products and circular business models

- Shifting to less material intensive options

- Improving resource efficiency and eco-design

Steps have been taken towards several of these solution pathways by the different EU bodies. For instance, Eurostat, European Environment Agency and Joint Research Centre have identified and monitored consumption, material, carbon and land footprints and legislative measures have also been adopted under the European Green Deal. What remains to be identified are policies and measures that will work to address consumption as a whole by reducing demand while at the same time increasing well-being and a just transition.

EU policies to address consumption-based emissions exist, but are not robust enough yet

There are many promising EU policy developments that aim to curb emissions connected to some categories of consumption. Among key initiatives is the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) which encourages greener production processes outside its borders by putting a price on imports of certain industrial goods manufactured in non-EU countries without a comparable price on carbon. Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR) is another promising piece of legislation that could reduce the climate impact of demand by ensuring products are not only manufactured sustainably by efficient use of resources, but are also durable. When it comes to addressing negative impacts of EU’s consumption outside of its borders, the Deforestation Regulation, Revised Regulation on conflict minerals, Regulation on prohibiting products made with forced labour on the Union market and the Directive on corporate sustainability due diligence are other good examples.

The EU’s long-term environmental objectives in the 8th Environment Action Programme include reducing material and consumption footprints as enabling conditions. However, what is still lacking in this complex policy landscape are clear goals, binding consumption targets and measures to shift consumption patterns and ensure social justice in the process of reducing emissions.

While some Member States have explicit references in legislation to avoid “exporting” negative environmental impacts to third countries, still a little over half (53%) of environmental impacts happen outside the EU borders. As part of our project, we are conducting case studies on the state of consumption-based emissions and policies to address them in Denmark, France and Sweden.

Denmark

In Denmark, about half of consumption-based emissions come from abroad, despite the Danish Climate Act principle to ensure that measures to decrease territorial emissions do not simply move them outside the country’s borders.

The same act aims at 70 percent reduction in territorial emissions in 2030 compared to 1990 and climate neutral society by 2050 at the latest.

France

More than half of France’s consumption-based emissions are imported. While France’s domestic emissions have decreased by a third (33%) since 1995, its imported emissions have increased by almost the same amount (32%).

Sweden

The Swedish Generational Goal adopted already in 1999, promises to solve major environmental problems in Sweden “without causing increased environmental and health problems outside Sweden’s borders.” However, based on the latest data, close to 60 percent of Sweden’s consumption-based emissions are generated abroad.

Despite Sweden not having a nationally set target, a large share of the Swedish municipalities already have a consumption-based target in place. This demonstrates that initiative and drive can also come from a local level, which could be cultivated with more support from the national level to help them advance their goals.

Our project will continue looking into the experiences from these countries and the full report including chapters on these case studies will be available later this year.

Lowering emissions is a global effort and EU could lead the way

The journey toward a sustainable future requires continued global collaboration and commitment from the EU and its Member States. Globally, we are heading towards breaching the 1.5 °C warming goal set by the Paris Agreement. On the EU level, the ambition level set for territorial emissions and goals for 2030 and 2040 can make a difference, especially if it also takes responsibility for imported emissions resulting from its consumption patterns and encourages more sustainable practices beyond its borders. There is a unique opportunity for the EU to emerge as a global leader in climate action. By adopting more stringent measures to address consumption-based emissions, the EU can not only reaffirm its commitment to the climate goals but also set examples for other nations to follow.

Our research work is ongoing, with expected publications by May 2024. Should you have some expertise on the topic and are interested in providing inputs relevant to our work, please do not hesitate to contact katarina.axelsson@sei.org

This summary article was published by SEI with inputs from IEEP.