AUTHOR: Laure-Lou Tremblay

Cities are planning how to increase urban green spaces for nature and for a healthy environment that is adapted to climate change. Pollinators are part of the nature that can flourish in urban green spaces.

IEEP and the Safeguard project in partnership with Eurocities led a conversation on how cities can integrate pollinator conservation and climate objectives into their urban greening planning in a recent webinar. The discussion gathered more than 50 EU city representatives and reverted on identifying how city planners and administrations can best integrate pollinator conservation and climate objectives into their urban greening planning. Participants discussed links between climate adaptation and biodiversity and pollinator conservation, which revealed some of the challenges that cities may face.

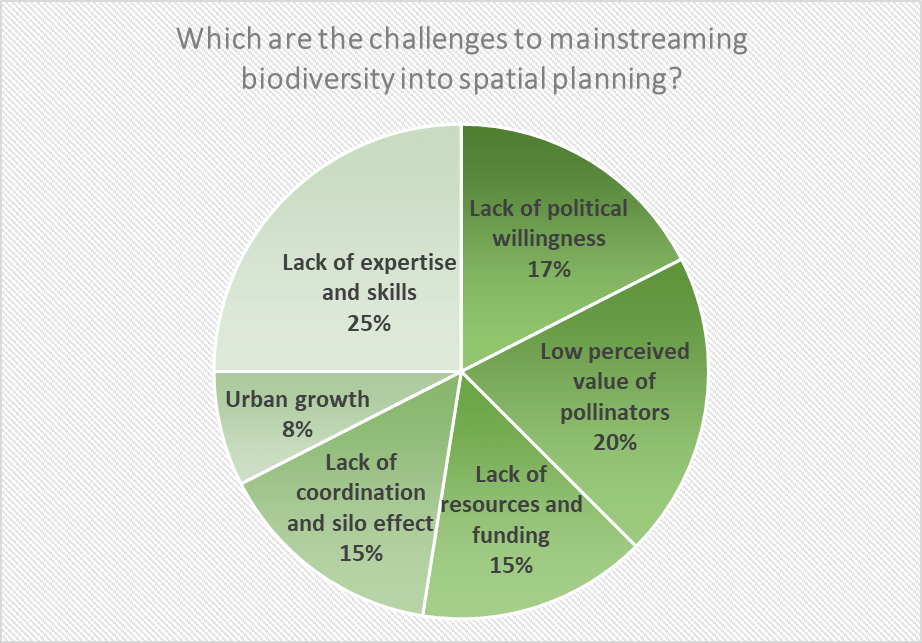

As revealed by a quick poll amongst participants, the lack of adequate skills and expertise appeared as the main challenge that city administrations may have to deal with for mainstreaming biodiversity into spatial planning. The discussion also highlighted that some cities are already actively linking their climate and biodiversity strategies and approaches, including a spotlight on pollinators.

Why should cities include urban greening in their plans and what does it have to do with pollinators?

The EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030 calls for cities and urban regions to produce urban greening plans – setting out how cities will increase urban green spaces for nature and for a healthy environment that is adapted to climate change.

2023 has been consistently breaking global temperature records, with September temperature being 0.93°C warmer than the September average for the period 1991-2020. The ‘urban heat island’ effect exacerbates the impacts of rising temperatures on urban citizens. Cities typically experience higher temperatures than rural areas because of all the heat-absorbing and emitting surfaces and the additional heat produced by buildings and traffic. Developing climate proof urban planning is becoming critical for most European cities. Green spaces and green vegetation along streets, on roofs and facades, is one of the most important ways to cool down the urban environment and provide people and nature with refuges from the heat.

At the same time, green spaces in urban and peri-urban areas can be important habitats for wild pollinators, providing them with food resources and foraging, reproductive, shelter and nesting sites that may not be available in surrounding agricultural areas.

How is global warming affecting urban pollinators?

Contrary to common misconceptions, heat is affecting wild pollinators very differently from humans, and these effects are poorly understood. The Safeguard project is contributing to fill some of these knowledge gaps, with a study conducted in Rome in 2022. Temperature was found to be the main driver of wild bee communities in the city. While warmer temperatures increased the abundance of individuals and the species richness, they led to the prevalence of certain functional traits among wild bees. While heat-tolerant wild bee species will benefit from increasing temperatures, these heat tolerant communities will be dominated by generalist (polylectic) and small-bodied bees, rather than the specialist (oligoleptic) bees and the larger bees such as bumblebees. Urban greening could play a pivotal role for wild pollinator communities by bringing temperatures down in key pollinator habitats within the city.

What can cities do to create synergies for pollinators and climate?

Urban greening offers opportunities to address both biodiversity and climate challenges in cities in complementarity. Paris has worked for several years to actively interlink its climate and biodiversity strategies in its urban planning, notably with the recent adoption of its ‘bioclimatic masterplan’, laying out urban planning rules for the 10 to 15 years to come. This bioclimatic plan carries the ambition to make Paris “a forerunner in a global way of conceiving the city to serve the ecological transition, both to transform and adapt the existing without giving up innovation and creativity”. The plan intends to develop ecological corridors within the city and increase urban greening, protecting and planting trees, private gardens and grounds, green roofs and walls, and public green spaces.

What challenges do cities face to integrate climate and biodiversity into urban planning?

During the discussion, Jonathan Sorel, advisor to the Mayor of Paris on public space, transport, mobility and nature in the city, underlined the city’s efforts to develop the skills of its urban greening staff to increase the ecological value of the city’s green space: “the ecological management of green spaces involves new skills – knowing how to select the right perennial plants and climate adapted trees, for example – and understanding – for example, not cutting down freshly planted saplings or retaining ecologically important plants whilst mowing an area. The Parisian employees are developing their skills and knowledge thanks to support from the administration.”

Urban planners may also have to deal with conflicting public perceptions on what urban (green) spaces should look like. In some cultures, the conflict between “neat and clean” aesthetics and pollinator friendly green space management is one of the biggest challenges that city administrations must deal with.

Anja Proske, project manager for the Berlin wildbee project at the German Wildlife foundation noted however that perceptions can change: “in Berlin, public perceptions have been changing over time, as illustrated by perceptions on mowing: citizens used to complain about the city not mowing – nowadays they complain about green areas being mown. It is important to repeat and simplify messages to effectively influence public perceptions on urban greening and pollinators.”

What next for urban greening and pollinators?

Cities are developing their urban greening plans now, with support from the European Commission and from associations like Eurocities. The EU Pollinators Initiative calls for the integration of pollinators in urban greening plans. The European Parliament is now drafting a response to the initiative: MEPs are pushing for ambition on pollinator conservation and monitoring in urban areas to increase their potential to “serve as models of coexistence between communities and pollinators”.

Cities are also anticipating the adoption of the proposed EU Nature Restoration regulation, which will require urban areas to achieve an increasing trend in the total national area of urban green space after 2030, provided ambition is kept in the ongoing negotiations.

As part of its focus on urban policy, the Safeguard project will soon follow up with a guidance document on pollinator monitoring and indicators for urban greening planning.

The presentations and the report from the webinar are available on the Safeguard’s media centre: Paris bioclimatic urban planning, Berlin wild pollinators project, scientific background (Costanza Geppert), presentation from ICLEI. The recording is available here.

Photo by Mathias Nevière on Unsplash