AUTHORS: Emma Bergeling and Emma Watkins

On New Year’s Eve this year, Stockholm city will break new ground by implementing a Zero Emission Zone (ZEZ). Low and Zero Emission Zones (LZEZ) are one tool to improve air quality to benefit the health of citizens and ecosystems. For successful implementation and local support, the socio-economic impacts of LZEZ must be understood.

This blog post outlines some indicative findings from an upcoming case study on Stockholm, prepared by IEEP in the context of a study for the Clean Air Fund.

Poor air quality is a health problem globally and in the EU. While the EU’s air quality has been improving, an astonishing 96% of the EU’s urban population are exposed to health damaging levels of air pollution, causing hundreds of thousands of premature deaths in Europe annually. The impacts are unequally distributed in the EU with higher pollution levels in disadvantaged regions.

There is also a disproportionately high impact on children, elderly, people in poor health, women, and socio-economic disadvantaged groups. The adverse impact of air pollution also has a negative impact in ecosystems.

Low Emission Zones can help the advance towards better air quality, and there is a growing body of literature on the positive environmental effects of LEZs. However, in some cities, their introduction has faced public resistance, highlighting the need for a deeper understanding on the socio-economic impacts of LEZs and best practices to tackle them and garner local support. For this purpose, IEEP is working with the Clean Air Fund, conducting five case studies on LEZs in Milan, Warsaw, Sofia, Brussels and Stockholm to feed into a final research paper to be published this autumn.

Stockholm has been – and continues to be – a pioneer in this area. The city implemented its first LEZ (LEZ1) already in 1996, making Sweden the first country in the world to do so. In 2020, a second, stricter zone was implemented (LEZ2).

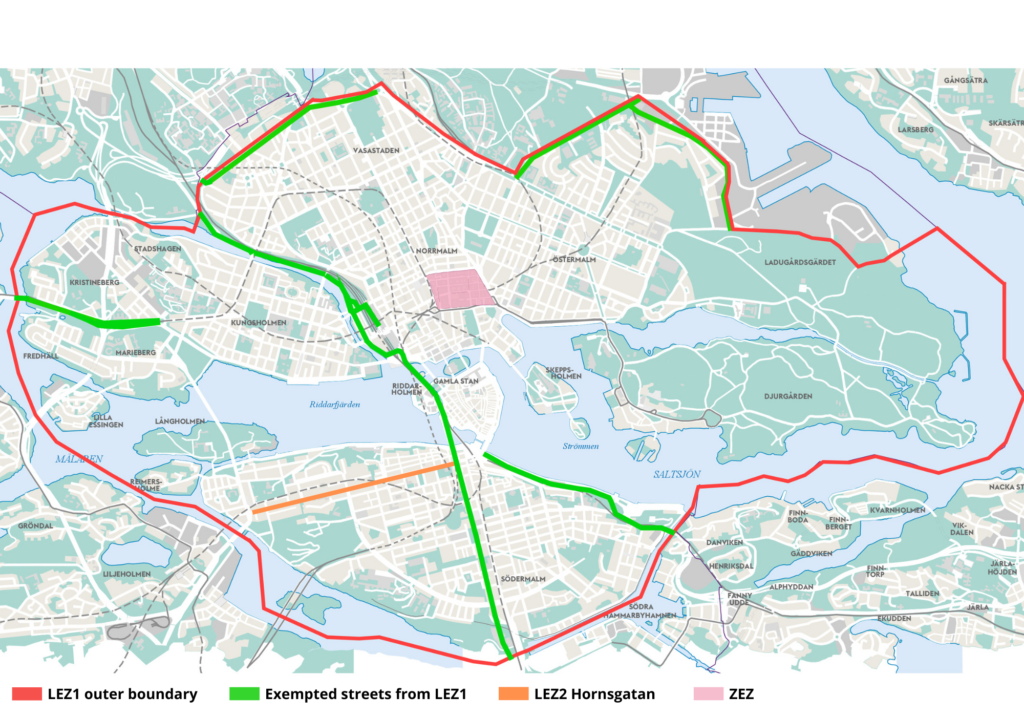

Now, in 2024, Stockholm is once again breaking new ground by implementing a Zero Emission Zone (ZEZ) covering an area in the city centre illustrated in pink below. Since it is the first of its kind, the European Commission reviewed the ZEZ and gave the green light to proceed in April 2024.

The consequence analysis and implementation of the ZEZ is informed by extensive stakeholder engagement, including the appointment of a dedicated employee for stakeholder engagement, meetings with numerous affected businesses and umbrella organisations representing transport enterprises and entrepreneurs, and consultation of the Stockholm Citizen’s Council (leading to some 2.700 responses).

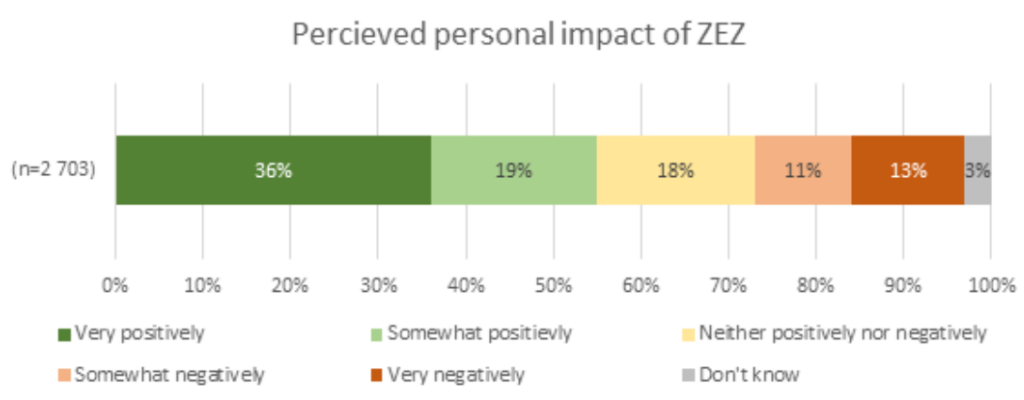

The results from the citizen consultation show that most respondents think they will be positively, or at least not negatively, impacted by the ZEZ (see figure below).

The estimated impact varies based on gender, location, and age. More men (15%) than women (10%) think they will be negatively affected. A much larger percentage of people under 50 (about 43.5%) believe they will be very positively affected, compared to 21-28% of those over 50.

The main perceived positive impacts are cleaner air, less traffic, and less noise. The main perceived negative impacts are:

1. Needing to take detours around the ZEZ

2. Increased difficulty driving to and within the City and Old Town

3. High cost of switching to an approved vehicle

4. More expensive transportation to and within the area.

While the consultations indicate a predominantly positive view of the ZEZ, in May 2024 the current opposition party announced their intention to appeal the decision to implement the ZEZ, arguing that it is tokenism, will be excessively costly for businesses, and the implementation timeline is too rapid. They also contend that no thorough impact analysis has been conducted.

In contrast, the governing parties emphasize the extensive consultation processes and investigations that have taken place, noting that notice of the ZEZ has been provided over two years before its implementation, providing sufficient time for adaptation.

Although the considerations needed for implementation of LZEZ differs between EU cities, the case of Stockholm offers some valuable insights. Three key ones are the importance of:

- Having an extensive, detailed, and continuous stakeholder consultation and outreach process, that begins as early as possible and is meaningful, leading to continuous exchange and betterment.

- Innovating together with key stakeholders where novel solutions are needed, for example by collaborating to maximize effective use of the loading capacity of transport within the zone.

- Make sure that there are – or create – accessible and affordable alternatives for clean mobility to and within the zone and consider distributional impacts. Ensure reasonable exemptions from the rules, for example for people with disabilities and emergency service vehicles.

The full Stockholm case study will be published end of June.

Image by David Vargas Carrillo on Unsplash