Authors: Céline Charveriat, David Baldock

This article is part of the Think 2030 report originally published in November 2018. The report is based on the work of more than 100 leading policy experts from European think tanks, civil society, the private sector and local authorities.

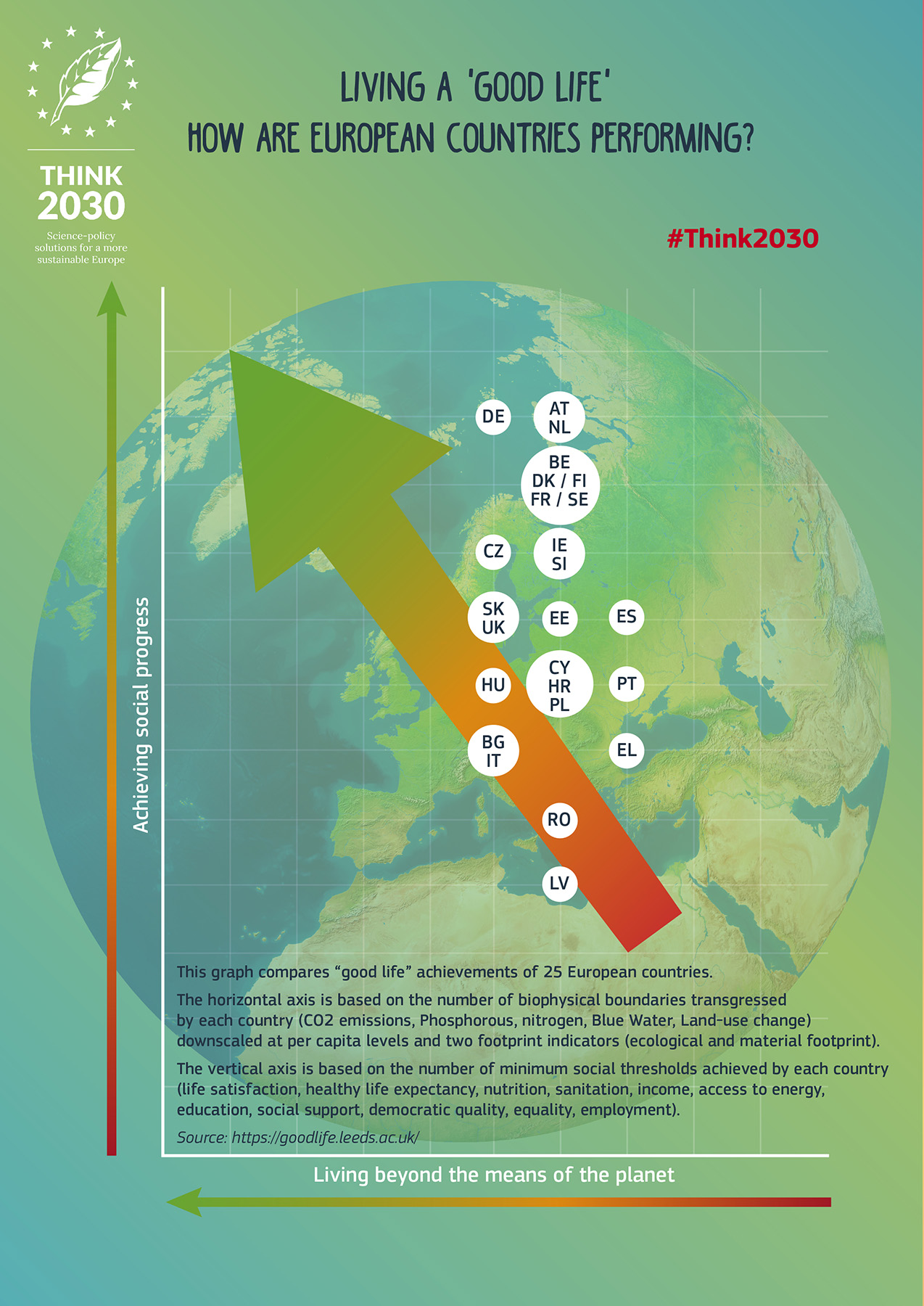

Europeans enjoy the longest life expectancies and Europe has some of the highest levels of human development in the world. No EU member state, however, is currently guaranteeing the well-being of its citizens while also staying within planetary boundaries.

The continent has a long way to go in achieving the social dimension of the Sustainable Development Goals, and it needs to do so while reducing its per capita material footprint.

All European countries are currently living well beyond the means of the planet, and yet they are failing to achieve some of the social objectives included in the SDGs.

All European countries are currently living well beyond the means of the planet (IEEP/Think2030, 2018). Full-resolution All European countries are currently living well beyond the means of the planet (IEEP/Think2030, 2018). Full-resolution |

Although access to a healthy environment is now considered by Eurostat as a component of well-being, there is insufficient understanding of the interactions between well-being, social outcomes, and the state of the environment: this is mirrored in the narrow focus and missed opportunities in terms of policy design.

Policies

The European Pillar of Social Rights, the priorities of which include equal opportunities and access to the labour market, fair working conditions, social protection and inclusion, is conceived as completely separate from environmental policies.

The EU social funds do not have an impressive record of addressing climate change, with only an estimated 7% allocated towards a low-carbon and climate-resilient economy through reform of education and training systems, an adaptation of skills and qualifications, upskilling of the labour force, and the creation of new jobs.¹

Likewise, environmental policy generally lacks credible tools and instruments to ensure its compatibility with social policies. While the circular economy is presented as inclusive, there remains scope for more concrete measures, beyond initiatives on food waste, which would foster inclusivity.

Moreover, the Social Rights Pillar is still incipient and a contested area of competence with Member States, weakening the incentive to embody it more strongly in the much more established environmental acquis.

Public health

The changing nature of the global burden of diseases suggests the need for much greater focus on the linkages between health and environment. Tackling growing worldwide air pollution, as well as other forms of pollution including noise, soil, water and food, should become a priority for European health policies in Europe.

| Urban air pollution is expected to be the main environmental cause of premature mortality worldwide in 2050 |

Urban air pollution is expected to be the main environmental cause of premature mortality worldwide in 2050. The EEA estimated that, in 2014, 399,000 premature deaths in Europe were attributable to exposure to fine particulate matter (PM 2.5), 75,000 to exposure to nitrogen dioxide and 13,600 to exposure to ground-level ozone.

There are major variations within Europe, with the highest rates of premature mortality in eastern and southern parts of the EU, the lowest in Sweden. The EU Court of Auditors estimated “hundreds of billions of euros in health-related external costs” in a review and critique of policy.² Even allowing for some overlap, there are about 400,000 such premature deaths in the EU, constituting the biggest single environmental health risk.

With pre-obesity affecting more than half of the EU’s population, changing diets and food consumption habits are becoming a health emergency. The issue of pesticides and endocrinal disruptors is now also high on the agenda, with increasing evidence of the health impacts of these substances.

New public health challenges also include the prevention of new epidemics or antibiotic-resistant infectious diseases linked with practices of the livestock industry. By 2050, drug-resistant infections could cause global economic damage on a par with the 2008 financial crisis.³

There is increasing recognition of the interest expressed by the public in supporting a transition towards a healthier diet, and the concept of the sustainable diet has rapidly gained ground amongst nutritionists. Under nearly all definitions, it includes a decline in the consumption of sugar, livestock products and alcohol – and an increase in fruits and vegetables.

In 2015, 119 million people, or 23.8% of the EU population, were at risk of poverty or social exclusion In 2015, 119 million people, or 23.8% of the EU population, were at risk of poverty or social exclusion |

Several Member States, including Denmark, are already experimenting with more assertive advice and labelling policies and experimenting with taxes on less healthy foods, such as sugary drinks.

Leaving no-one behind

In 2015, 119 million people, or 23.8% of the EU population, were at risk of poverty or social exclusion. Risk factors include:

- being a woman

- being young

- living in a single-headed household with dependents

- living in rural areas

- having a low educational attainment

- having been born in a non-EU country.

Severe material deprivation – an absolute poverty measure – affected 37.5 million people or 7.5% of the EU population in 2016. This was not evenly distributed within Europe, with over a quarter of the Romanian population, for example, living on less than $5.50 a day, the highest poverty rate in the EU.⁴

According to the (partial) evidence available, low-income households tend to live in a less healthy environment than higher-income ones and suffer from multiple sources of vulnerability.

They suffer from poorly insulated housing, more affected by dampness, noise and air pollution, lack of access to green recreational facilities and to fresh and nutritional foods. They also have greater challenges in terms of affording energy and mobility.

All these factors have a proven negative impact on their health and life expectancy. The case of air pollution is well documented, but it is likely to be a more widespread issue.

For example, there is growing evidence that the lack of access to nature is a contributing factor in poor mental health and obesity among low-income groups.⁵

Their capacity to cope with shocks, such as natural disasters, life-threatening diseases, or sudden increases in prices of essential goods are also more limited.

Addressing multidimensional inequality: Towards a just transition

The impact of the sustainability transition on employment is a critical issue. Estimates predict that global unemployment could rise to 25% by 2050⁶ because of technological change rather than environmental constraints.

Impacts of the twin technological and sustainability transition on production systems will not be fairly distributed across gender, geographical location and age and might exacerbate already existing inequalities in Europe.

| There is a growing awareness about the need for a just transition in the energy sector |

There is a growing awareness about the need for a just transition in the energy sector. In the EU, the coal sector provides jobs to about 240,000 people, with 180,000 employed in the mining of coal and lignite and 60,000 working in coal- and lignite-fired power plants.

The European country that records the highest number of coal mining jobs is Poland, with about 115,500 people employed in coal mines and related businesses. In all other countries, less than 30,000 people are employed in the coal industry, representing less than 0.6% of total national employment. Compared to other sectors, the scale of the challenge is, thus, relatively small and impacts will be regionally concentrated.

Compared to the coal industry, the scale of the transition required for a decarbonisation of the transport sector and its impacts on the automobile industry is very different, as a much higher number of jobs are involved. Thirteen million Europeans work in the automobile sector in manufacturing, services and construction, representing 6.1% of total EU employment.

Compared to the coal industry, the scale of the transition required for a decarbonisation of the transport sector and its impacts on the automobile industry is much greater Compared to the coal industry, the scale of the transition required for a decarbonisation of the transport sector and its impacts on the automobile industry is much greater |

Agriculture is another sector that will undergo a massive transformation.

Some subsectors might be hit particularly hard. Various studies that have looked into the climate impact of farming and livestock have concluded that a 50% reduction in livestock capacities will be necessary for farming to help achieve existing climate goals for 2030 and 2050.

In fact, the RISE foundation identified a safe operating space for livestock and found that in order to reach EU climate targets, livestock in the EU needs to be reduced by 74% in 2050.⁷

Growing income inequality in Europe also needs to be factored in.

There is a correlation between income levels and carbon footprint.⁸ Environmental taxes have to be designed to ensure behavioural change amongst the top income group as well as to minimise impacts on income and asset inequality.

Conversely, tax reform as a key policy instrument for redressing social inequalities⁹ needs to factor in the environmental considerations, not least because of the links between the exploitation of natural resources and fiscal evasion, money laundering and corruption.

Social transfers also need to be taken into account. The changing nature of work – due to technological change, as well as ageing – and the crisis of classic retirement models will make the issue of the new entitlements, such as the universal basic income, a key debate for the next period. Ensuring their design contributes, rather than hinders, sustainability will be important.

Generational equity is a key topic for Europe’s sustainability transition. The EU’s current economic model tends to disadvantage the youth.

| In Europe, people under 24 are the most at risk of severe material deprivation |

In Europe, people under 24 are the most at risk of severe material deprivation. Due to higher rates of unemployment and the stagnation of workers’ income, the income of young people has only recently reached pre-crisis levels while people aged 65 or more registered a 10% increase in their income.¹⁰

Correspondingly, there seems to be a correlation between age and carbon footprint, not only because many older people simply have more money to spend, but also because they tend to use less energy-efficient products.¹¹ Moreover, environmental degradation, depletion of resources and climate change will also have disproportionate impacts on those who will live through to 2100.

The consequences of an ageing population also need to be better understood. With the percentage of the population over 65 reaching close to 30%,¹² there will be implications not only for resource allocation, employment and environmental footprint, for example in health care but also for gender equality due to the unequal burden of care.

Scenarios that foresee the use of robots and machines to take care of the elderly or children could be hard to square with the need for less consumption of energy and materials overall. Greening of the care economy might, therefore, become a greater priority.

Not all citizens place the same burden on the environment, and policy development needs to reflect this appropriately.

Should the ‘polluter pays’ principle apply more systematically at the household level for example?

A report by the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) found per capita greenhouse gas emissions for a Londoner in 2004 were the equivalent of 6.2 tonnes of CO2, compared with 11.19 for the UK average.¹³

The rural northeast of England, Yorkshire and the Humber, were singled out for having the highest footprints per capita in the UK. At the same time, however, rural populations often play an important role in providing ecosystem services.

Globally, 67% of people will be living in cities by 2050. In Europe, the rate of urbanisation is expected to reach 80%.¹⁴

| A large proportion of the action required will need to be initiated and managed within communities. Local ownership and engagement are key |

The geographical distribution of the population has an impact on transport, the supply of services and the environment more generally.

Average demographic density in Europe reached 120 inhabitants per square meter, ranging from three people per square meter in Iceland and over 16,000 in Monaco.¹⁵ While internal migration within Europe is low, there are still rapidly growing regions and shrinking ones. Such changes need to be factored into sustainable urban planning, as low-carbon infrastructure and adaptation.

A large proportion of the action required to bring about the transition will need to be initiated and managed within communities, whether they are large urban conglomerations or remote villages. Local ownership and engagement are key. EU frameworks, funding, R&D, sectoral targets and other mechanisms can support a web of localised actions. Much of the focus will be on urban areas, including major cities, where a growing share of the population live. But it is important that the specific needs of rural areas are not overlooked in the process.

Little is known about potential interactions between the sustainability transition and other forms of inequality, such as gender or minorities. Such considerations need to be integrated to ensure the co-benefits of the sustainability transition on other social justice issues.

| Recommendations for well-being 2030The social dimensions of Europe’s environmental policy must be recognised as central to delivering a legitimate sustainability transition. Critical measures at the EU level should include:Design a comprehensive environmental health strategy, providing a coherent framework for addressing public health threats linked most urgently with air pollution, which disproportionately harms the life chances of poorer communities, and supported by new regulations for chemicals and medicines.Strengthen the European Social Pillar of Rights to support a Just Transition, through a range of social interventions needed to secure jobs and livelihoods covering all potentially affected sectors, communities and regions.Integrate sustainability considerations in the reforms of income and wealth taxation and social protection systems, which will be necessary to address rising inequalities and demographic changes.Build the resilience of cities, rural communities and the wider environment through more effective adaptation strategies and action plans to address climate change.Ensure the adequate representation of the interests of both youth and future generations, by establishing an EU Guardian for future generations.Close the knowledge gaps regarding the interlinkages between poverty, multidimensional inequality (generation, geography, gender, race, income) and sustainability in Europe through research and funding for socially innovative projects. |

References

1. Own calculations based on Ricardo (2017). Climate mainstreaming in the EU Budget: preparing for the next MFF.

2. European court of auditors (2018) Special report (23/2018). Air pollution – Our health still insufficiently protected.

3. World Bank (2016) Press release: By 2050, drug-resistant infections could cause global economic damage on par with 2008 financial crisis.

4. Brookings Institution (2018). Romania: Thriving cities, rural poverty, and a trust deficit.

5. Mutafoglu, K. & Schweitzer, J. P.(2017). Nature for Health and Equity. Briefing produced by IEEP for Friends of the Earth Europe: Role of nature for children and adolescents.

6. Daheim C, & Wintermann Ole Bertelsman Stiftung 2050: The Future of Work. Findings of an International Delphi-Study of The Millennium Project.

7. Rise foundation (2018). What is the Safe Operating Space for EU livestock?

8. In Europe, the share of the top income group in income (45%) broadly correlates with its share in the carbon footprint (37%). This is also true for the bottom income group (6% in income and 8% in footprint).

9. Darvas, Zsolt and Wolff, Guntram B. (2016). An anatomy of inclusive growth in Europe. Bruegel Blueprint Series 26, October 2016.

10. International Monetary Fund (2018). Staff discussion note. Inequality and Poverty across Generations in the European Union.

11. Zagheni, E. (2011). The leverage of demographic dynamics on carbon dioxide emissions: Does age structure matter?. Demography, 48(1), 371-399.

12. Eurostat (2017). People in the EU – population projections.

13. IIED (2009). Cities produce surprisingly low carbon emissions per capita.

14. Eurostat (2016). Urban Europe — statistics on cities, towns and suburbs.

15. Statistica (2017). European Union: Population density from 2007 to 2017 (in inhabitants per square kilometer.

About Think2030Think2030 is an evidence-based, non-partisan platform of 100 policy experts from European think tanks, civil society, the private sector and local authorities.Based on a series of papers covering all major environmental challenges, the 30 actions, contained in the #think2030 Action plan, will enable European citizens to live prosperous, peaceful and healthy lives by 2050, while sustaining the 80% reduction in per capita resource use.For more information visit www.Think2030.eu |